[Editor’s note: This letter was penned by Tim Price, London-based wealth manager.]

In his book What works on Wall Street, James O’Shaughnessy analysed a variety of strategies that delivered market-beating returns in the US stock market.

Value investing proved to be one of the most outstanding.

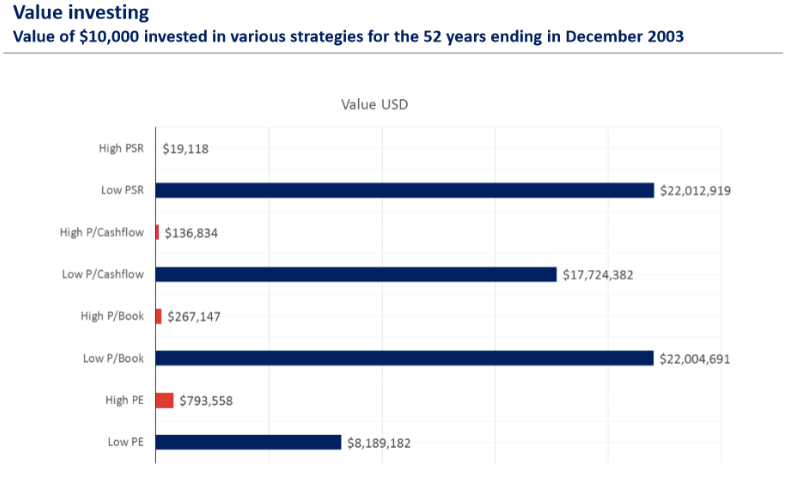

O’Shaughnessy took a variety of metrics – the price/sales ratio (PSR), price/cashflow, price/book and price/earnings – and then collated the 50 stocks from the broad US market which displayed the highest, and lowest, for each metric.

He then annually reweighted his two lists, and ran this portfolio of ‘growth’ and ‘value’ over a period of 52 years, ending in December 2003 (shortly before the third edition of his book was published in 2005).

The results of O’Shaughnessy’s experiment are shown below.

(Source: ‘What works on Wall Street’ by James O’Shaughnessy)

Your hypothetical $10,000, starting 52 years ago, invested in the 50 stocks with the highest price/sales ratio (PSR) compounded up to $19,118.

That may seem like a pretty good return, until you see what you could have won, by owning the 50 stocks with the lowest price/sales ratio from the same market.

Your hypothetical $10,000 ended up with a terminal value of $22,012,919.

Did someone say ‘value beats growth over the longer term’?

Similar outperformance comes whether you’re assessing stocks by price/cashflow, price/book, or price/earnings.

In each case, over the longer term, ‘value’ doesn’t just beat ‘growth’. It wipes the floor with it.

Perhaps the 52-year period in question was a statistical anomaly. But we doubt it.

More likely, the statistical aberration is the recent outperformance of bonds versus stocks, during an environment in which the supply of bonds has never been higher in recorded human history.

The perversity of the O’Shaughnessy study is that it flies in the face of the idea that markets are rational or efficient.

Logically, by taking more risk – in paying up to own ‘growth’ stocks at higher multiples than the market average – one should expect to achieve higher returns.

But O’Shaughnessy shows that this didn’t happen.

Which highlights the attractiveness of ‘value’ as an investment strategy at a time when many equity markets have become, in our view, unsustainably expensive as a result of monetary stimulus and the success – so far – of ‘Smart Beta’ and ‘growth’ strategies.

‘Value’ investing typically offers investors what Benjamin Graham called a “margin of safety”, on the basis that high quality companies are being bought at a discount to their inherent value.

‘Growth’ stocks, on the other hand, are clearly being bought at a premium.

The renowned ‘value’ investor Seth Klarman once said,

“The hard part is discipline, patience and judgment. Investors need discipline to avoid the many unattractive pitches that are thrown, patience to wait for the right pitch, and judgment to know when it is time to swing.”

With bonds now being essentially an uninvestable asset class, now is the time to swing. But only for the right kind of stocks.