[Editor’s note: Tim Price, London-based wealth manager, is filling in for Simon today.]

After the fall of France in 1940, Great Britain, under Churchill, fought on against the Nazis, virtually alone. Although she would ultimately be joined by the overwhelming military and economic might of the United States, for a period she fought more or less friendless, with her back to the wall. In the process of prosecuting the war, quite apart from the human toll upon her military and citizenry, Great Britain bankrupted herself. Her polity and economy would be irrevocably changed in the pursuit of final victory.

What was her reward? Early attempts at joining the European Economic Community were rebuffed. In November 1962, General de Gaulle hosted the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan at Rambouillet, south of Paris. The French leader was unyielding, and the French ‘Non’ to British entry to the EEC came as a bitter blow. Andrew Marr in his ‘History of Modern Britain’ writes that

“At one point, Macmillan broke down in tears of frustration at the Frenchman’s intransigence, leading de Gaulle to report cruelly to his cabinet later: ‘This poor man, to whom I had nothing to give, seemed so sad, so beaten that I wanted to put my hand on his shoulder and say to him, as in the Edith Piaf song, “Ne pleurez pas, milord.”

Marr tells another interesting story about the birth of the EU, some seven years before the Rambouillet humiliation. Representatives of ‘the Six’ founding EU nations – France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands – met at a small coastal town in Sicily called Messina. Britain declined to send a minister but instead dispatched a middle-ranking civil servant, Russell Bretherton. At the end of the negotiations, so the story goes, Bretherton stood up and told the assembled politicians:

“Gentlemen, you are trying to negotiate something you will never be able to negotiate.But if negotiated, it will not be ratified. And if ratified, it will not work.”

Inaudible though it may be to the tin ear of Remoaners, the EU does not appear to be working today. Its immigration policy is a murderous disgrace; its banking system is teetering on insolvency; its economy is stagnating, with terrible consequences for the young and unemployed at its periphery; full steam ahead, cry its leaders, as impervious

to legitimate criticism as the RMS Titanic was to icebergs.

Now we see the full dynamism of this trading behemoth at work, as the Walloons – an ancient race of space monkeys that featured in several early episodes of ‘Doctor Who’– have done their best to scupper a trade deal between Canada and the 28 separate member states of the European “Union”. If this is an integrated economic bloc, we’d hate to see a dysfunctional bureaucracy of squabbling tiny-minded cretins.

Better off out would seem to be the order of the day. And still EU “leaders” like Donald Tusk nurse fond hopes that Britain might yet reverse its decision to leave, and elect to stay in the burning building instead.

Some hope. Brexit has conclusively delivered a hammer-blow to European competitiveness by facilitating a 16% devaluation of sterling – a currency depreciation that virtually every government on the planet has been trying to pull off but which the European “Union” is structurally incapable of delivering.

One country that has managed to conclude a trade deal with the European “Union” is Vietnam – a country of 94 million people, many of them young, and most well educated.

In a 2012 OECD assessment of maths, reading and science skills among 15 year-olds, Vietnam scored more highly than France, the UK, and the US. Vietnam is rapidly industrialising and becoming the destination for FDI across Asia. It is also highly competitive – its average monthly wages are one third those in China.

Yet its stock market is cheap.

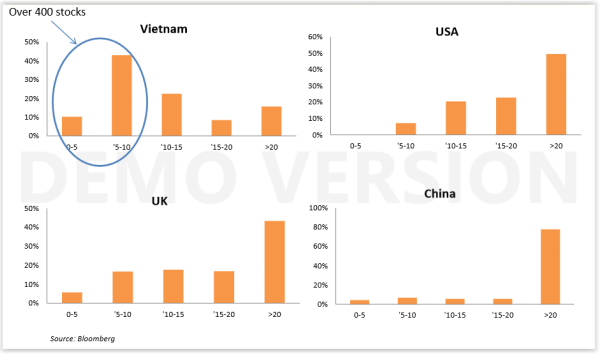

The charts below show the p/e ratios for the stock markets of Vietnam, the United States, the UK and China.

Valuation opportunities: p/e ratio distributions for Vietnam, US, UK and China

Fully half of the Vietnamese stock market trades on a p/e ratio of less than 10.If only there were some way of accessing this value. Happily, there soon will be. SSI Asset Management already manages the Vietnam Value and Income Portfolio, a specialised investment fund that is the single largest holding in our global value fund and that has delivered 33.8% returns in GBP since its inception in December 2015.

SSI will shortly be launching the Vietnam Value Income and Growth Fund in a UCITS format. The anticipated p/e of the fund is 10x, return on equity 20%, and expected dividend yield 5.1%.

Or you could invest in the euro zone: a failing economic and political bloc that is arguably already in a Depression.

Pay money. Take choice.