This information is general guidance and is not tax advice. Before acting, please consult a qualified financial and legal advisor familiar with your particular situation.

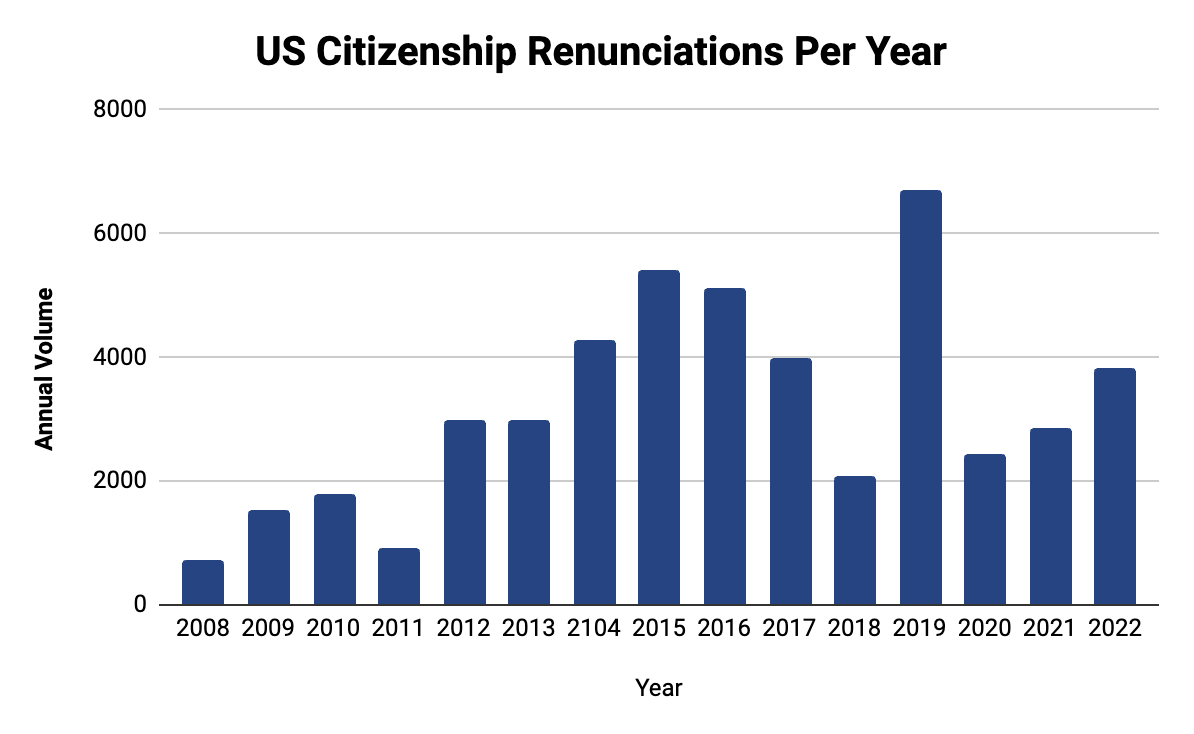

With every US presidential election, there are thousands of people – on both sides of the aisle – who threaten that they’ll renounce their citizenship and leave the country. But the majority of them don’t follow through on these threats.

Yet after the 2016 presidential election, around 4,000 US citizens did renounce in 2017. And outside of the pandemic period, this appears to be a growing trend.

However, politics isn’t the only contributing factor. A combination of high taxes, combined with the complexity of complying with US tax laws, are two key reasons for US expats, in particular, to consider renouncing their citizenship.

It’s important to understand that moving away and formally renouncing your citizenship are two very different things. One is temporary – or it can be; the other is permanent.

One still ties you to the American financial system (because Uncle Sam taxes you on worldwide income, wherever you live). The other frees you forever, but relegates you to alien status.

One can be cheap and easy — you just hop on a plane. The other is expensive (legal and/or application fees, and in some cases an exit tax) and cumbersome (as you have to acquire a different citizenship first).

Still, every year, more people give up their US citizenship.

Outside of politics and taxes, people renounce for personal or career reasons. In addition, others do it for reasons related to financial privacy, or because of taxation without representation:

(Note: US citizens must always file US taxes, regardless of where they live and pay applicable taxes. Only limited tax breaks are available to them, e.g. the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion.)

When FATCA came out in 2010, renunciation applications started climbing. US citizens were finding that the costs of being a US citizen — in the form of regulations, reporting requirements and restrictions — started to exceed the benefits.

And the fact that the Bolsheviks want to squeeze you even harder is (almost) beside the point: US tax rules are already onerous enough that if you are living outside America’s borders, you’re being penalized for it.

Source: US Treasury Department data

Considering renouncing? Make haste slowly

Formally giving up your US citizenship is not something to be done lightly. And especially if you’re still young, you may want to think very carefully before locking yourself out of the US job market – and making accessing your motherland more difficult.

Unless your new citizenship will be from Canada or one of the countries participating in the Visa Waiver Program, you will have to get a US visa at a US consulate – an arduous process.

It behooves you to take a big-picture view of the situation, and really weigh how helpful (or potentially unhelpful) renunciation might be. Factor in your source of income, your ties to the United States (including to family members or business partners), and whether you can really find what you’re looking for elsewhere.

And even then, wait some more…

But if you’re ready to pull the trigger, then the next key question is…

Will you have to pay an exit tax upon renouncing?

This is one of the most important things to understand about renunciation: If you’re what’s known as a ‘covered expatriate’, i.e. you meet certain financial requirements, then you may have to pay an exit tax.

You are a covered expatriate if any of the following conditions are met:

- You have a net worth of $2 million or more;

- You have an average net U.S. income tax liability (what you owe) of greater than $190,000/year (in 2023) for the five-year period prior to expatriation; or,

- You fail to certify that you have complied with all US federal tax obligations for the preceding five years.

As for your net worth, the $2 million includes the aggregate value of your worldwide assets, not just your US ones. And that includes pensions and your home.

Embedded into the law, however, are a few ways to get out of being considered a covered expatriate. If both of the following conditions are true, you are not a covered expatriate:

- Your relinquishment of US citizenship occurs before you turn 18 and a half; and,

- You have been a resident of the US for fewer than ten ‘taxable’ years before you relinquish.

Another way to get out of the designation is to be born with dual citizenship. (We cover the conditions for this in the pages of Sovereign Confidential.)

An exit tax may apply to green card holders as well…

If you have been a permanent resident of the US for at least eight years (or more precisely, eight out of the last 15 years), then the same “exit tax” rules apply to them as to other US citizens, should they decide to renounce.

The IRS will consider individuals in this category as “covered expatriates” if they decide to give up their permanent residency in the US.

Beware: there is a LOT more to renouncing your citizenship than meets the eye…

And that’s why you need Sovereign Confidential, our flagship intelligence and diversification service. Members benefit from comprehensive deep-dive guidance on every aspect of renouncing your citizenship.

For starters, you’ll ideally need to obtain an alternative residency (and ideally citizenship) to avoid becoming stateless, either on the basis of your ancestry, or via investment.

In addition to helping you understand the complexities of whether you’re a ‘covered expatriate’, the product also explores the various ways in which you can avoid this dreaded status.

We also cover the respective rules and differences between how Roth and Traditional IRAs are treated if you’re a covered expatriate – versus when you’re not.

In addition, we also included detailed case studies of people who successfully expatriated, along with the strategies they used to legally lower their exit taxes owing.

To learn more about the benefits of joining Sovereign Confidential, click here.