[Editor’s Note: This letter was written by Tim Price, London-based wealth manager and frequent Sovereign Man contributor.]

Léon Walras is the patron saint of modern economics.

In other words, he was a clueless failure who hijacked immutable principles from the world of physics and misapplied them to the economic realm.

The result, predictably enough, is that modern economics doesn’t work.

It doesn’t work because it masquerades as a science when it is really just a combination of dogma and very crude modelling. The modelling doesn’t work because garbage in equals garbage out.

Sadly, this doesn’t stop the governor of the Bank of England from advocating overly simplistic policies in a highly complex world.

What is alarming today is that almost nobody dares challenge the mandate or even ongoing existence of central banks as prime fixers of prices in the financial markets. (Spoiler warning: price fixing doesn’t work.)

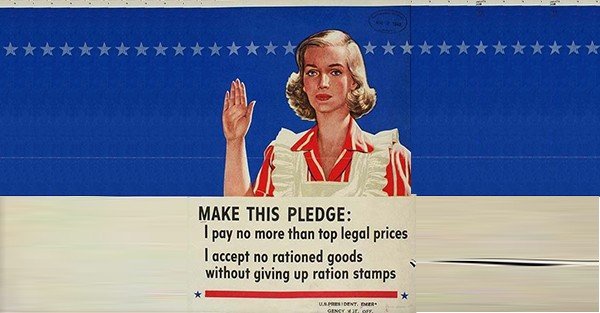

“Attempts to control and fix prices and wages span most of recorded history,” writes David Meiselman in the foreword to the definitive history of economic hubris, ‘Forty centuries of wage and price controls’ (Robert Schuettinger and Eamonn Butler).

“Price and wage controls cover the times from Hammurabi and ancient Egypt 4,000 years ago to this morning..

“The experience under price controls is as vast as essentially all of recorded history, which gives us an unparalleled opportunity to explore what price controls do and do not accomplish.

“I know of no other economic and public policy measure whose effects have been tested over such diverse historical experience in different times, places, peoples, modes of government and systems of economic organization..

“The results of this investigation would merit attention for the light it sheds on economic and political phenomena even if wage and price controls were no longer seriously considered as tools of economic policy.

“The fact that wage and price controls exist in many countries and markets and are being seriously considered by others, including the United States, compels attention to the historical record of wage and price controls this book presents.

“What, then, have price controls achieved in the recurrent struggle to restrain inflation and overcome shortages? The historical record is a grimly uniform sequence of repeated failure. Indeed, there is not a single episode where price controls have worked to stop inflation or cure shortages.

“Instead of curbing inflation, price controls add other complications to the inflation disease, such as black markets and shortages that reflect the waste and misallocation of resources caused by the price controls themselves. Instead of eliminating shortages, price controls cause or worsen shortages.

“Despite the clear lessons of history, many governments and public officials still hold the erroneous belief that price controls can and do control inflation. They thereby pursue monetary and fiscal policies that cause inflation, convinced that the inevitable cannot happen.

“When the inevitable does happen, public policy fails and hopes are dashed. Blunders mount, and faith in governments and government officials whose policies caused the mess declines. Political and economic freedoms are impaired and general civility suffers.”

Interest rates across the developed markets have been kept at emergency levels (and all time historical lows) for seven years. Do we think that allowing banks to access essentially free money is more or less likely to give rise to the sort of malinvestments that caused the financial crisis in the first place?

If you believe that the answer is ‘less likely’, there is a job at your local central bank with your name on it. (It will help secure the position if you have previously worked at Goldman Sachs.)

David Meiselman again:

“[D]espite all the evidence and analyses, many of us still look to price controls to solve or to temper the problem of inflation.

“Repeated public opinion polls show that a majority of U.S. citizens would prefer to have mandatory controls. If the polls are correct, and I have no reason to doubt them, it must mean that many of us have not yet found out what forty centuries of history tell us about wage and price controls.

“Alternatively, it raises the unpleasant question, not why price controls do not work, but why, in spite of repeated failures, governments, with the apparent support of many of their citizens, keep trying.”

In the aftermath of this weekend’s horrible events in Paris, religious dogmatism is rightly condemned. If only dangerous economic dogmatism could be similarly repudiated.