In late January of the year 98 AD, after decades of turmoil, instability, inflation, and war, Romans welcomed a prominent solider named Trajan as their new Emperor.

Prior to Trajan, Romans had suffered immeasurably, from the madness of Nero to the ruthless autocracy of Domitian, to the chaos of 68-69 AD when, in the span of twelve months, Rome saw four separate emperors.

Trajan was welcome relief and was generally considered by his contemporaries to be among the finest emperors in Roman history.

Trajan’s successors included Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, both of whom were also were also reputed as highly effective rulers.

But that was pretty much the end of Rome’s good luck.

The Roman Empire’s enlightened rulers may have been able to make some positive changes and delay the inevitable, but they could not prevent it.

Rome still had far too many systemic problems.

The cost of administering such a vast empire was simply too great. There were so many different layers of governments—imperial, provincial, local—and the upkeep was debilitating.

Rome had also installed costly infrastructure and created expensive social welfare programs like the alimenta, which provided free grain to the poor.

Not to mention, endless wars had taken their toll on public finances.

Romans were no longer fighting conventional enemies like Carthage, and its famed General Hannibal bringing elephants across the Alps.

Instead, Rome’s greatest threat had become the Germanic barbarian tribes, peoples viewed as violent and uncivilized who would stop at nothing to destroy Roman way of life.

Corruption and destructive bureaucracy were increasingly rampant.

And the worse imperial finances became, the more the government tried to “fix” everything by passing debilitating regulation and debasing the currency.

In his seminal work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon wrote:

“The story of its ruin is simple and obvious; and instead of inquiring why the Roman empire was destroyed, we should rather be surprised that it had subsisted so long.”

Gibbon was right. These trends are incredibly powerful. And once they reach a tipping point, they’re almost impossible to stop.

Similarly, though, no one has the ability to look into a crystal ball and predict with any certainty when it will all finally break down.

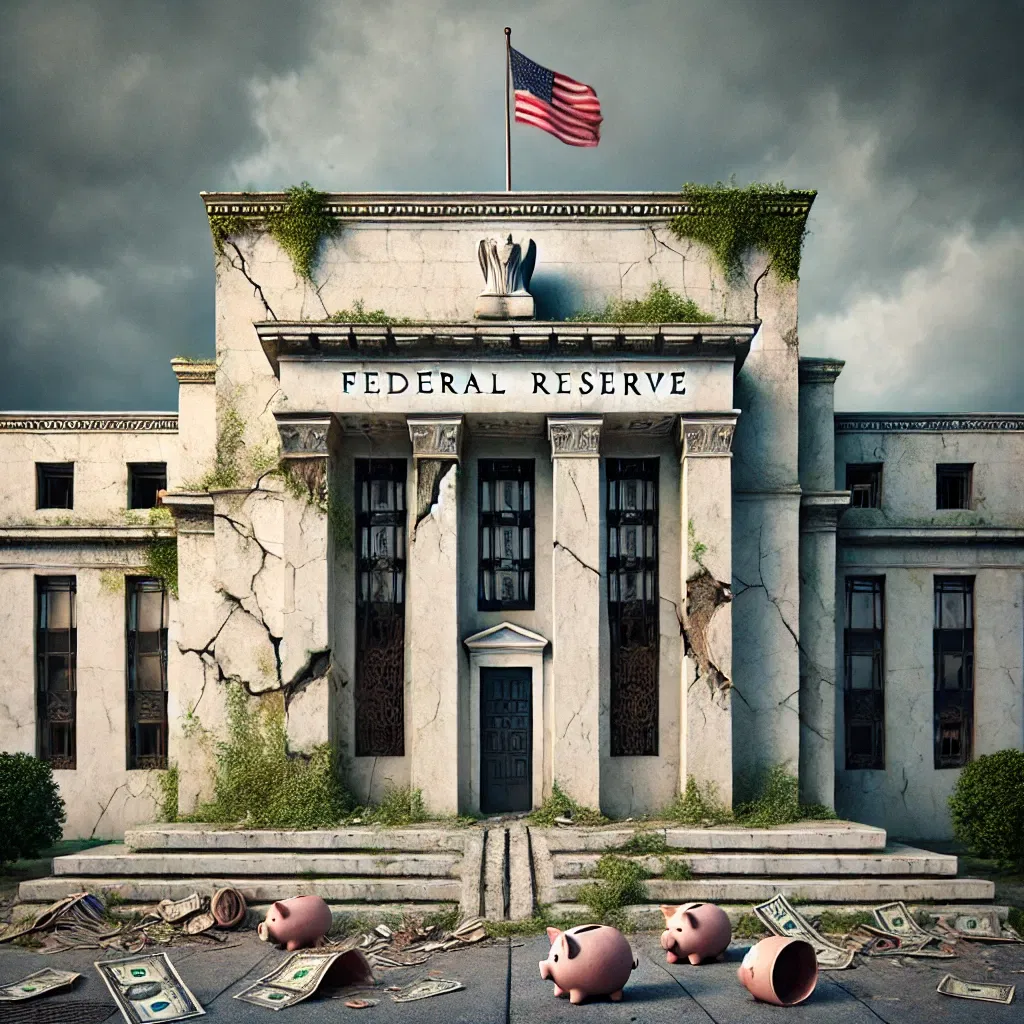

In today’s version of the Roman Empire, the United States, we can see similar circumstances.

The debt level is now rapidly closing in on $20 trillion, well in excess of 100% of GDP.

And even under the government’s most optimistic estimates, this debt is growing at a far more rapid rate than the economy could ever hope to expand.

We can see a central bank that is nearly insolvent.

We can see a commercial banking system that, even in the opinion of its own regulators (most recently the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis), is still at significant risk to succumb to a major crisis.

We can see Civil Asset Forfeiture levels that have increased to astonishing rates.

These trends are pretty obvious, and they have been building for years.

And history shows that, whenever governments reach these tipping points, they tend to rely on a very limited playbook.

In ancient times, the Romans imposed wage and price controls under penalty of death.

In our modern era, governments default on the obligations they’ve made to taxpayers (for example, social security and pension payments).

They impose capital controls, preventing you from engaging in even the most basic financial transactions like withdrawing money from your own bank account.

They grab assets and retirement savings. They freeze accounts.

This isn’t theory or conjecture– it’s reality. Each one of these examples has actually taken place in the developed world in the past few years.

It’s not crazy or radical to acknowledge these simple facts.

Actually, denying them and pretending like these problems don’t exist seems pretty crazy.

And understanding the truth doesn’t mean that the world is coming to and end. Far from it.

But it does make sense for rational, thinking people to take some simple steps to distance themselves from the consequences of such obvious trends.

For example, if your banking system is deeply flawed, don’t keep all of your money there. Easy. Why take the chance?

Instead, consider holding a bit of cash, or perhaps move some funds to a more conservative, well-capitalized bank that’s backed by a government with zero debt.

If the fundamentals of your currency are pitiful and your central bank is nearly insolvent, don’t keep 100% of your assets denominated in it.

Consider diversifying into other currencies or owning some real assets, like productive land, profitable businesses, precious metals, cash-producing real estate.

If your government is flat broke and losing money every year, don’t keep all of your assets there, especially your retirement savings.

Consider structuring a better retirement plan where you have the latitude to move funds outside the conventional financial system and away from their easy reach.

These concepts ensure that, no matter what happens (or doesn’t happen) next, you’ll always be in a position of strength.

There may be good emperors and bad emperors, devils and saints.

And the consequences of the trends they’ve created may come to pass tomorrow, next month, next year, or perhaps (by some miracle), never at all.

But it’s hard to imagine you’ll be worse off for having a portion of your savings in a safe, well-capitalized bank as opposed to an illiquid one.

It’s hard to imagine you’re worse off because it’s more difficult for frivolous plaintiffs to sue you.

Or that the completely legal steps you’ve taken have reduced your tax bill.

Or that your new retirement plan is safer and exposed to more lucrative investment options than ever before.

Rational, thinking people don’t ignore such obvious risks. They understand that the biggest risk of all is doing nothing.

The solutions are simple, effective, and absolute no-brainers. All it takes to implement are the proper tools, the right education, and the basic will to take action.