April 28, 2014

London, England

[Editor’s note: This letter was written by Simon’s colleague Tim Price in the UK, who is currently Director of Investment at PFP Wealth Management]

As contrarian investments go, we’re probably in three of the biggest.

As regular readers will be aware, gold is one – subject to the proviso that the term ‘investment’ may be linguistically and semantically insufficient in the context of what gold really represents: an escape from the insanity of massive and historically unprecedented money-printing throughout the western economies.

During the biggest collective currency debasement in history, comparatively scarce and undoubtedly finite monetary metal surely needs little further explanation.

Russia is another, admittedly not assisted by current events in Ukraine. Nevertheless, cheap valuation is cheap valuation, whatever transpires in the geopolitical realm.

The third, and perhaps the most intriguing, is Japan.

People have a tendency to extrapolate. When a trend has been sufficiently long-lasting, that tendency to extrapolation becomes very powerful.

In 1989, the Nikkei 225 Stock Index peaked at just under 39,000. Now, 25 years later, it sits at around 14,500. Over the last quarter of a century, it has lost nearly two thirds of its value.

QUESTION: Is the Japanese equity market riskier, or less risky, today than it was 25 years ago, when it was priced 24,000 index points higher ?

When Benjamin Graham, widely regarded as the godfather of value investing, wrote ‘The Intelligent Investor’ in the 1940s, you could hardly give US stocks away.

After the grinding economic torture of the Great Depression and the lost hopes of the 1930s, nobody was interested in buying listed equities. Which, needless to say, made them very attractive.

By the end of 1949 when ‘The Intelligent Investor’ was published, stocks were widely reviled. Between 1950 and 1960, the US stock market rose by 250%.

But that was then, and this is now.

Today, US stocks are priced for something close to perfection. Since the Fed has driven deposit rates down to zero and artificially suppressed the yields on Treasury bonds, equities have become the investment choice of both first and last resort for just about everybody.

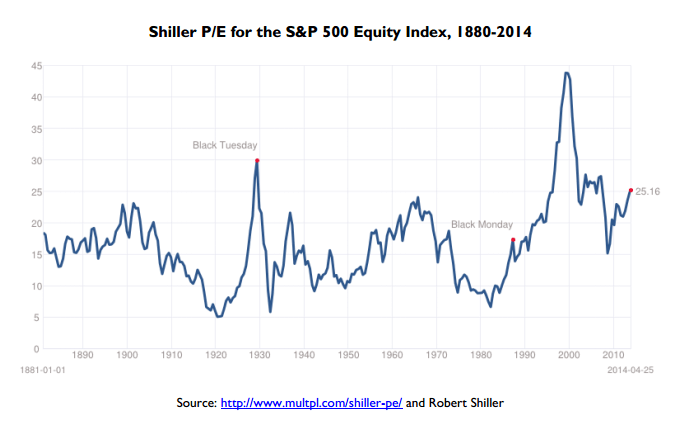

Right now the cyclically adjusted Shiller P/E ratio for the S&P 500 today stands at over 25. Its historic range is 20% to 60% lower. And each time this happened in the last 133 years, it was ultimately followed by a crash in valuations as steep as 80%.

So we believe US stocks are pricey.

Japanese stocks, on the other hand, are not. Fully half of the members of Japan’s Topix Index trade below book value.

As Neptune’s Chris Taylor points out, investing in Japan is all about the companies, and not the country.

But perceptions about the country may also be misleading. In his view, there are two fundamental structural changes driving company earnings growth in Japan.

One is what he calls “the global special situation”: Japan is in the midst of a long-term shift from being an export-driven economy to a model of global multinational production and sales.

In other words, Japanese businesses are not merely exporting from Japan; they are operating internationally and selling from those international bases.

The second is what he calls “System Reset – Japan version 2.0”.

Whether you believe the second characteristic depends on the strength of your belief in politics. The “System Reset” case rests on dramatic economic policy shifts based on the December 2012 Japanese election results.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is the first Japanese Prime Minister for 25 years to have an internal LDP majority. He also has a majority in both the Upper and Lower houses of the Japanese parliament.

The largest domestic opposition party has 58 seats to the LDP’s 315.

Abe, in other words, has a strong popular mandate to effect change.

His much vaunted ‘three arrows’ policy includes monetary easing, government spending, and supply side reforms.

While we have reservations about the efficacy of quantitative easing, we would concede that it is more likely to boost credit provision within a functioning banking system (i.e. Japan’s) rather than within a broken one (i.e. those of the UK and Euro zone).

And while Japan’s first flirtation with QE back in 2001 was somewhat half-hearted, nobody can really challenge their commitment to the cause this time round.

The Bank of Japan has pledged to double the Japanese monetary base within two years. One thing we know about QE is that it if the recent history of the US and UK markets is any guide, it tends to make stock prices rise.

And if you do it aggressively enough, relative to other practitioners, it also tends to weaken your currency.

Between the 16th December 2012 election and the end of 2013, the Japanese yen fell by 20% versus the US dollar.

QUESTION: if you think the BoJ will continue to be successful in devaluing the yen, does that make Japanese stocks (and exporters) look more or less attractive ?

FOLLOW-UP QUESTION: if you do decide to buy Japanese stocks, should you hedge your yen exposure ?

Notwithstanding its significance as that of the world’s third largest economy, the Japanese stock market has some catching up to do. Since September 30, 1982, the MSCI World Equity Index is up by 26 times. The S&P 500 Index is up by 34 times. Japan is up by just 2.3 times.

QUESTION: which of these markets would you rather own today ?