November 3, 2014

London, England

[Editor’s note: This essay was penned by Tim Price, a London-based wealth manager and editor of Price Value International.]

Strange things are happening in the bond market.

Few of them are stranger than the reports Jeremie Banet, a French fund management colleague of former Pimco executive Bill Gross, quit the bond business altogether to sell croques-monsieur from a food truck.

Bill Gross, whose management style has been described as “bullying”, had reportedly told in front of Pimco’s entire investment committee that, “I never understand what you’re saying. Ever.”

With those credentials, Monsieur Banet is supremely qualified to become the next chairmen of the Federal Reserve. And if so, he has his work cut out for him.

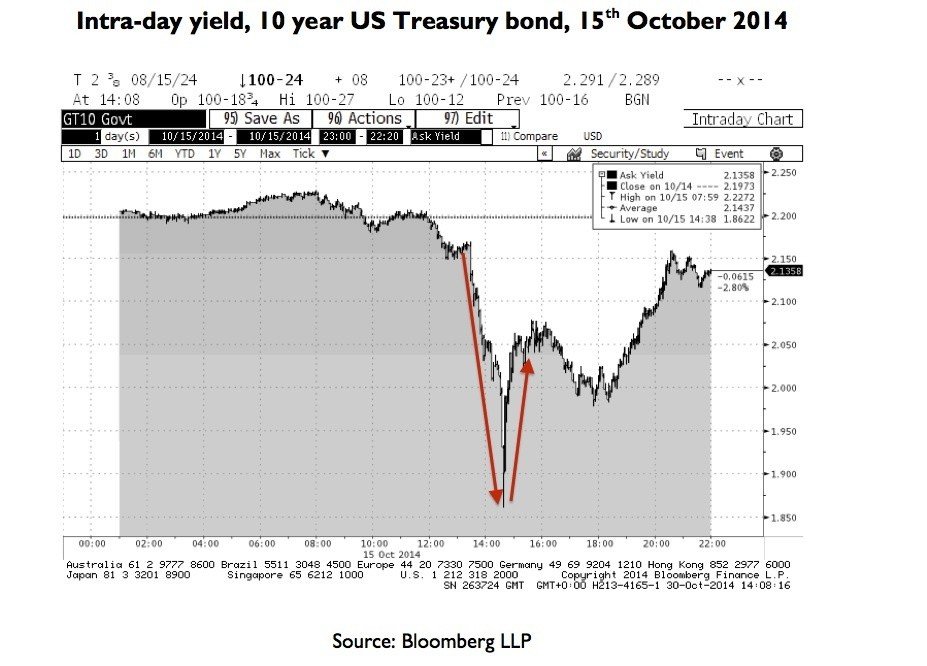

Consider the sort of volatility that the 10-year US Treasury experienced on 15th October.

Having begun the day sporting a 2.2% yield, the 10-year note experienced an extraordinary surge in price that took its yield down briefly towards 1.85%.

Later in the same session the buying abated, and the bond closed with a yield of roughly 2.14%.

During the same trading session, equity markets sold off aggressively (the UK’s FTSE 100 index, for example, closed down almost 3% on the day).

What accounts for such melodrama? Analyst Russell Napier takes up the story:

“On October 15th 2014, if only for a few short minutes, market forces broke out and the failure of central bankers was briefly evident.”

“There is a very simple lesson that when the markets finally break through the manipulation they move to price in deflation and not inflation. This is key because it means financial repression has failed.”

These days, you don’t tend to hear the words ‘failure’ and ‘central bankers’ in the same sentence (unless the topic happens to be Zimbabwe). But perhaps the omniscience and omnipotence of central bankers is somewhat overstated.

On October 29th, the US Federal Reserve followed a long-rehearsed script and announced that it had “decided to conclude its asset purchase program [also known as QE] this month.”

The Economist’s Buttonwood column described it as “Letting go of Daddy’s hand,” and cautioned, “[W]e may indeed get to see QE4 rolled out. Daddy might have let go of the market’s hand for the moment but he’s still close by.”

That coinage nicely speaks to the juvenilisation to which markets have been reduced during six long years of financial repression, interest rate manipulation, and the unprecedented expansion of central bank balance sheets.

Only the asset purchases have abated (for now): the financial repression, one way or another, will go on.

Whether the asset purchases have really disappeared or merely been suspended will be a function of how risk markets behave over the coming months and years.

And although our crystal ball is no more polished than anyone else’s, we would not be surprised to see petulant markets rewarded with yet more infusions of sweets.

Our fundamental views are clear: bonds are already grotesquely expensive, yet may become even more (we’re not investing in “the usual suspects” so we don’t much care).

Most stock markets are pricey – but in a world beset by QE (and prospects for more, in Europe and Asia) which prices can we really trust ?

By a process of logic, elimination and deduction, out of major, conventional asset classes, only quality listed businesses trading at (or ideally well below) a fair assessment of their intrinsic worth offer any semblance of value or attractiveness.

Pretty much everything else amounts to nothing more than paper, prone to arbitrary gusts from some very powerful, and very windy, bureaucrats.

We note also that former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, no doubt looking to polish his legacy, managed to front-run the Fed’s QE announcement by pointing to the merits of gold within a government-controlled, fiat currency system.

Strange days indeed.