June 15, 2015

London, England

[Editor’s note: This letter was written by Tim Price, London-based wealth manager and frequent Sovereign Man contributor.]

Today marks the end of the most notorious example of fiscal insanity in modern times.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe today begins a process to “demonetise” its now irrelevant currency, the Zimbabwe dollar.

Between now and September 30, Zim dollars can be exchanged for the US variety.

Holders of Zim dollars should not get too excited. As the FT reports, accounts “with balances of zero to Z$175 quadrillion will be paid a flat US$5”.

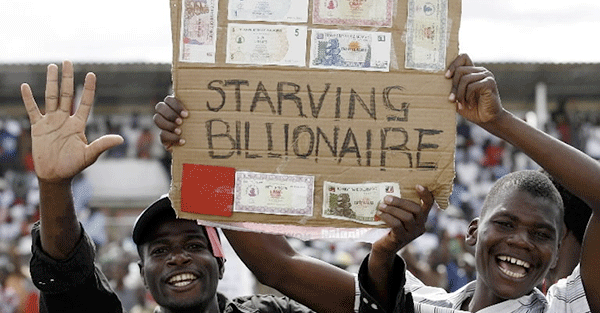

As the proud owner of a Z$100 trillion note, I may not take up this generous offer. A Z$100 trillion note has far more comic potential even than a US$5 replacement.

The Central Statistics Office of Zimbabwe stopped publishing estimates of price rises in 2008, when inflation was rising at an annual 231 million percent.

But it couldn’t happen here. Martin Wolf of the FT has said so, so it must be true.

And yet the suspicion lingers. What happens when trillions of dollars, pounds, euros and yen get printed out of thin air? How can money printing be the answer? If it were, Zimbabwe would be the richest country on earth.

So here we stand, seven years into the post-Lehman financial era, and base rates still squat at around zero. Government debt loads are even more creakingly immense.

Much of the banking system, especially in Europe, remains unreconstructed.

Emergency central bank support for the financial sector has bought us seven years. It doesn’t seem to have bought us much else.

And Greece remains a thorn in the side of the euro zone grand project.

More ominously, there are signs of fault lines emerging in the bond markets of the euro zone.

Sharp sell-offs over recent weeks have led many to ask whether a 40-year bull run in interest rates may finally be on the turn.

Bond market volatility has been exacerbated by regulator-imposed curbs on bank inventory.

Like the other major central banks, the US Federal Reserve, through the aggressiveness of its own stimulus and price distortion, has painted itself into an uncomfortable corner.

Art Cashin, UBS’ director of floor operations, told CNBC: “While the Fed is talking about being measured and data dependent, they’re potentially playing with fire here because they could start spontaneous combustion that they can’t control.”

Bonds remain outrageously overvalued, in most cases, despite the recent sell-off, which could be a precursor of more dramatic moves to come. But a number of major stock markets are hardly cheap.

Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e ratio for the S&P 500 index stands at 27 times. Its long run average is 16.6.

The US broad market has only been more expensive than today twice in history – in 1929, and in 2000. Neither was an auspicious time to be buying US stocks.

So what is the rational investor to do?

The current titanic struggle between deflation (the markets) and inflation (central banks) has been well described as a tug-of-war.

On some days, deflation appears to have the upper hand.

On others, inflation seems to be in the ascendant.

At other times, both forces appear to be in an uneasy state of near stability.

We think the ultimate outcome is more likely to be inflationary, since inflation answers the debt problem in the most politically feasible way.

Either way, the outlook for most bond markets seems poor to us, given that supposed safe havens in the debt world actually have lousy creditworthiness.

And the very substance of credit derives from the concepts of belief and trust. Once confidence in the system cracks, it is unlikely to return in a hurry.

What is the pragmatic solution ?

Given the outlook for both bond and stock markets, we wrote a few weeks ago that we believed it was to own:

- Shares in successful businesses from all over the world, on an index-unconstrained basis

- With competent and honourable management

- Who think like owners because they are owners

- With companies that have little or no debt

- And crucially, not to overpay for shares in such businesses, but to maintain the ‘margin of safety’ that comes from buying them at hugely attractive multiples.

Interest rates haven’t been this low for 5,000 years. Bonds as an asset class are now compromised and no longer offer risk-free returns.

Equities seem to be the more attractive asset class but it makes sense to be highly selective, and to avoid the more egregiously overvalued, instead favouring lower risk, higher quality, truly defensive stocks.

We are clearly inhabiting a strange and unprecedented financial environment. There has been much malinvestment, and in our view far too much ill-conceived and certainly untested monetary stimulus.

As Robert Louis Stevenson once observed, “Sooner or later everyone sits down to a banquet of consequences.”

Tim Price is a principal at London-based Price Value Partners, a new global value equity fund, which invests precisely on the basis that Tim describes above.