[Editor’s note: Tim Price, London-based wealth manager and co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio, is filling in for Simon today.]

Here’s some food for thought.

There’s been so much discussion over the past few years, and 2016 in particular, about the roaring US economy and stellar performance of US companies.

As an example, we are constantly told about the cash piles that US companies have hoarded around the world.

This is meant as an indicator that US companies are accumulating huge profits.

It turns out this is not entirely true.

As Andrew Lapthorne of Societe Generale pointed out at his bank’s investment conference last week, that giant pile of cash is concentrated in the hands of a few companies.

While the largest 25 US companies are rolling in cash, the remaining 99% of corporate North America barely has any.

Specifically, the 25 largest companies in the US have an average cash balance of over 150% of their average debt levels.

But the cash average for every other company averages about 16%, a nearly 10x difference.

It’s a similar story of concentration when it comes to corporate profitability.

The biggest US companies remain very profitable, with an average return on equity that has been very stable at around 16% since the early 1990s.

But the trend of profitability for the remaining 2500 US stocks has been deteriorating for the past two decades, with an average return on equity falling to just 6%.

In other words, all the supposed success of US companies is extremely concentrated, and the health of the overall US market has been obscured by the performance of a handful of mega-cap companies that are selling at record levels.

As value investors, this gives us reason to stay away.

Value investors are bargain shoppers; we’re on the lookout for high quality assets, especially profitable, growing businesses, whose shares are selling at an obvious discount.

As Warren Buffett has pointed out countless times, most people by nature are bargain shoppers.

Everyone wants a great deal, whether it’s on a new car, family vacation, or online purchase.

For some reason, though, that psychology doesn’t apply to investment decisions.

It’s as if people feel more comfortable buying shares of a company that’s popular, expensive, and overvalued.

In the long run, value investing is what matters.

Stock prices fluctuate wildly from day to day, and even year to year.

But a value investing strategy dramatically outperforms in the long run.

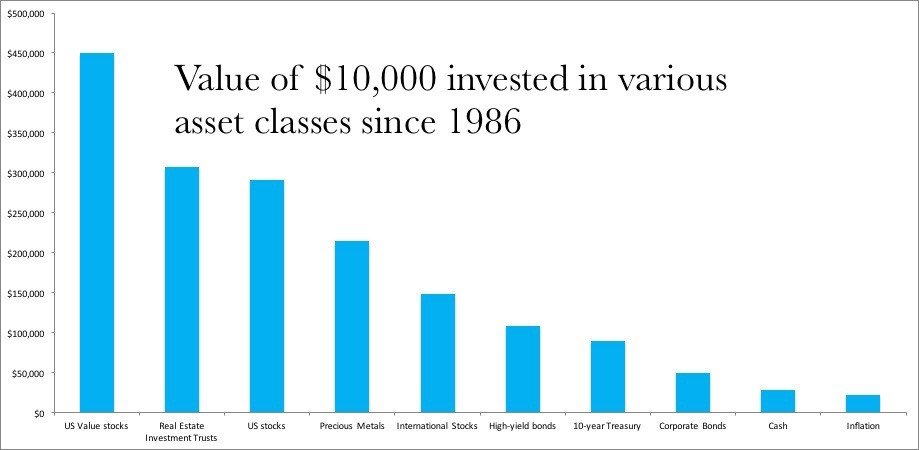

As the following chart shows, $10,000 invested in the broader US stock market in 1986 would be worth $291,334.08 today.

That’s a fantastic return on investment.

But had you invested in value stocks, that same $10,000 would be worth $449,358.86 today, over 50% more.

Value stocks beat other asset classes as well—bonds, international stocks, precious metals, real estate, etc.

The approach works.

The difficult part, of course, is finding that bargain discount business, particularly in a sea of overvalued share prices.

But this is when an astute investor starts looking abroad. There are always pockets of value somewhere in the world.

Japan remains a great example today.

Having endured a more than two-decade deflationary recession, Japanese corporate balance sheets are now among the strongest in the world.

Yet given the still inexpensive share prices, Japanese stocks offer something comparatively rare in modern investment markets: a genuine margin of safety.

One intriguing indicator of the Japanese stock market is its low “dividend payout ratio” compared to other countries around the world.

A company’s dividend payout ratio represents the portion of its profits that it pays to its shareholders each year.

Some companies pay a higher portion of their profits to shareholders, while others retain their profits to reinvest back in the business.

Japanese companies, on average, have THE lowest dividend payout ratios in the world, at less than 40%.

By contrast, British companies’ dividend payout ratios exceed 100%. This is hardly sustainable.

As an example, British company GlaxoSmithKline, popular among large equity income funds, made £1.9 billion in 2015… but paid out £3.8 billion in dividends that same year.

No company can indefinitely continue to pay its shareholders more than it makes in profit.

The Japanese stock market is at the other extreme.

Flush with cash, Japanese companies are now able to return capital to shareholders, either through dividends, or through share buybacks.

(When a company uses its cash pile to buy its own stock, the share price tends to rise, which benefits shareholders.)

Stock buybacks in Japan are now accelerating.

Yet unlike in the US and UK where companies go into debt to fund their dividends and share buybacks, Japanese companies can buy back their shares and pay dividends out of cash and profits.

(It may not be too much of a surprise to learn that Japan represents the single largest country exposure in our value fund.)

I’m not trying to encourage you to rush out right now and buy Japanese stocks.

The larger point is that successful investors do not constrain themselves by something as antiquated as geography.

There’s always a great deal to be had somewhere in the world.

And putting in a little bit of effort and education to find it can make an enormous difference in your portfolio.